Marquetry: An Endangered Art

There is something hypnotic about watching a craftsperson lay veneer. Paper-thin sheets of wood, each one revealing its grain like a fingerprint, fitted together so precisely that the joints disappear. A single piece of veneer means little. But in skilled hands, dozens and hundreds come together to create patterns and narratives through grain and colour.

This is marquetry, the art of creating pictures and patterns in wood veneer. Yet this cherished craft is disappearing fast. Listed on the Heritage Crafts Red List of Endangered Crafts, fewer than a hundred practitioners in the UK maintain it as a professional skill. Without intervention, this centuries-old technique risks extinction within a generation.

An Art Born from Scarcity

In ancient Egypt, precious woods were rare and expensive. Marquetry began as a solution to this scarcity. Craftspeople learned to slice timber into impossibly thin sheets, stretching these scarce materials to cover larger surfaces than solid wood would allow.

By the Renaissance, the technique had evolved into decorative craft. Dominican monks at Mount Oliveta near Siena used it to adorn church furniture and religious objects, inventing specialised tools like the ‘donkey’ - a cutting frame still used today. The craft spread through Europe, each region adding its own vocabulary of pattern and technique.

The 17th-century French cabinetmaker André Charles Boulle perfected marquetry at the courts of Louis XIV, combining tortoiseshell, brass, and exotic veneers into furniture of unprecedented sophistication. English masters like Thomas Chippendale and Thomas Sheraton brought the technique to Britain, where it flourished in design workshops and cabinetmaking studios serving the aristocracy.

Example of Boulle Marquetry, Shani Evenstein, CC BY‑SA 4.0

Industrialisation and the Decline of Marquetry

By the Victorian era, marquetry had become a hallmark of high-end furniture, synonymous with quality and sophistication. When industrialisation arrived, factories ceased the opportunity to quickly and cheaply produce simple decorative marquetry borders, to decorate table edges and cabinet panels, making furniture with elements of marquetry affordable to the middle classes. But intricate pictorial marquetry required artistic sensibilities that could not be mechanised: selecting veneers for grain direction and colour, skilfully matching patterns, making constant adjustments during the fitting process. Without the speed advantage of machines, handcrafted marquetry could not compete on price, and commercial demand collapsed.

What further contributed to the decline of marquetry was both the materials and the knowledge becoming scarce. Marquetry had long relied on exotic veneers such as ebony from Africa, rosewood from Brazil and satinwood from India, all prized for their dramatic colours and grain patterns. As colonial trade routes shifted and environmental concerns grew, these materials became expensive and difficult to source. In addition, the deep knowledge required, understanding which species work for which applications, how different woods behave when sliced paper-thin, which adhesives suit which grains, was passed person to person in workshops rather than taught in formal institutions. This meant the skill remained concentrated among a small number of practitioners who had access to those informal apprenticeships.

In 1952, the Marquetry Society was founded to preserve this intricate craft. Nowadays, the organisation reports an ageing membership with few young people entering the field. Training pathways have collapsed. City and Guilds - Britain's primary vocational qualification body withdrew its marquetry qualifications in the early 2000s due to a lack of enrolment.

Keeping The Tradition Alive

When Mark Boddington founded Silverlining, he understood that if marquetry was to survive as a living craft, it needed workshops actively creating demand, training practitioners, and proving the technique could meet contemporary standards. His approach was rooted in respect for the craft itself: marquetry would not be outsourced or treated as occasional decoration but practiced daily by specialists dedicated to mastering it. Today, Silverlining has a dedicated marquetry department where craftspeople work exclusively on projects requiring the highest levels of precision and artistry.

Silverlining's marquetry can be found in private residences and superyachts alike, from coffee tables and wall panels to bespoke cabinetry, each piece demonstrating the technique's contemporary relevance.

Poppy Pawsey, Silverlining's marquetry specialist and winner of the Emerging Artisan of the Year Award presented at the BOAT Artistry and Craft Awards, brings both traditional skill and material innovation to the technique. Since joining Silverlining Furniture in February 2023 without prior experience in furniture-making, Poppy has demonstrated an unwavering dedication to her craft. Her contributions to high-profile projects, including the bespoke games table for the superyacht Kismet, have showcased her precision, creativity, and artistic growth.

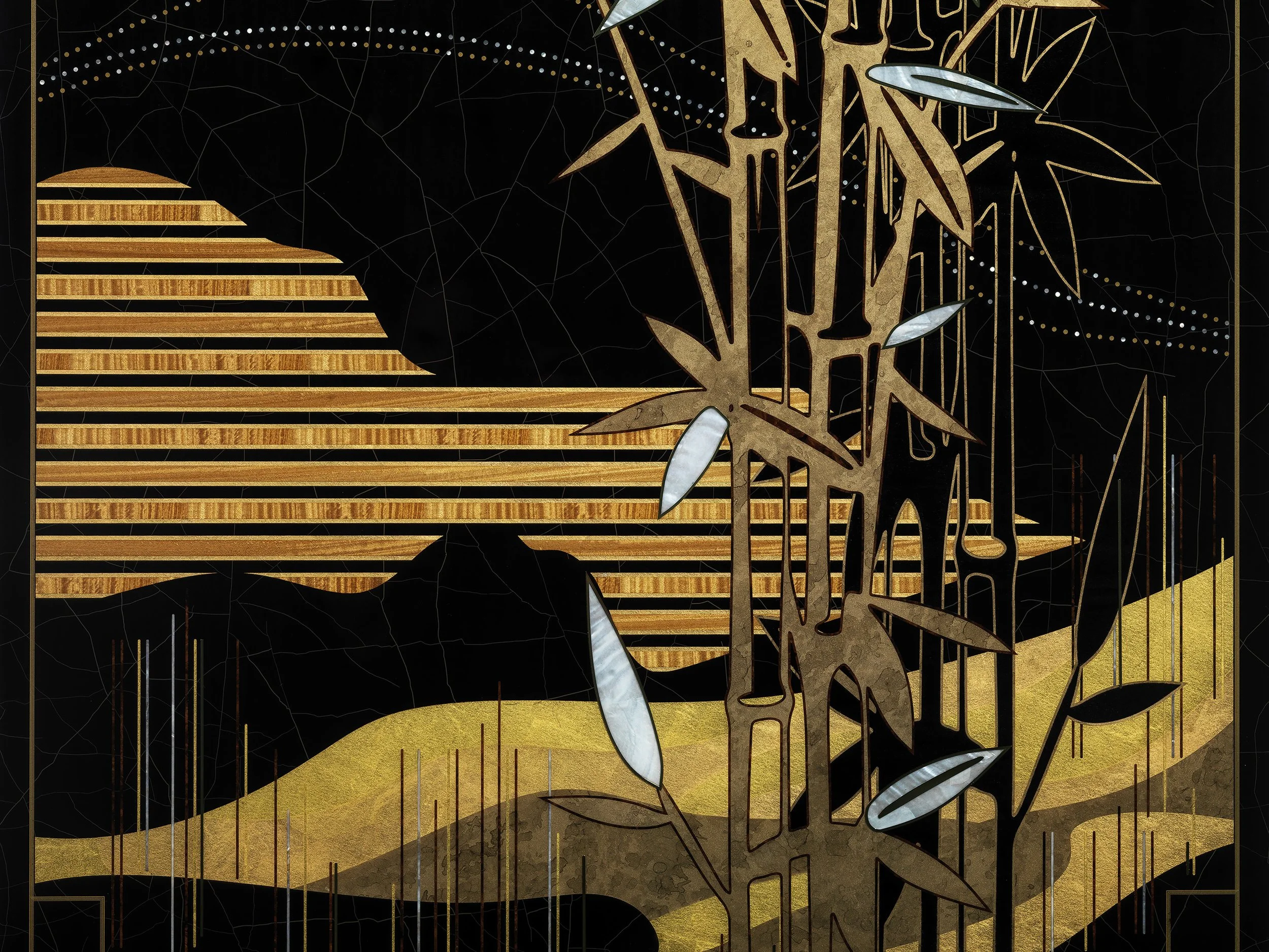

Also found on the Kismet superyacht are chinoiserie panels combining traditional motifs with laser-cut precision. Flora and fauna is depicted in hand-selected native veneers, each panel a composition of hundreds of individually shaped pieces. For marine environments, Silverlining adapts both adhesives and finishes to meet technical demands: marine epoxy glue replaces standard adhesives, whilst specialist lacquer systems protect against moisture, salt, and UV exposure. The marquetry itself remains unchanged, demonstrating how traditional craft can be applied across environments when paired with the right material specifications.

The oak oyster marquetry is the main feature of the Cracked Earth Coffee Table, inspired by Namibian salt flats. Each oak oyster displays natural starburst patterns that cannot be replicated. Consecutive veneers from the same log are book-matched for natural symmetry, creating patterns that echo geological fissures. The marquetry sits within bronzed channels, ancient technique meeting modern metalwork, requiring hours of meticulous hand work.

Leaf marquetry is the defining element of the Autumn Drift design sample, where individual veneers are selected for grain direction, creating the illusion of veins and natural movement. As light catches different grain angles, the leaves seem to shift. Each leaf represents hours of precise cutting and fitting.

The technique also transforms waste into beauty. Offcuts from larger projects become marquetry material. Burls and figured timber unsuitable for structural use find purpose as visual focal points.

Why It Endures

Marquetry thrives at Silverlining because it has been sustained by decades of investment in people, equipment, and expertise. That depth of capability enables Silverlining’s craftspeople to work at the highest level, taking on designs so intricate that few workshops would attempt them. Every client who commissions these pieces plays a part in securing the technique’s future. This is how craft is sustained: through a community of craftspeople, clients, and advocates who choose to master it, to commission it, and to carry it forward.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign-up to receive our newsletter and discover our stories, collections and latest innovations.